The path to AI doctors and lawyers is nearer and even worse than you think

AI will soon dominate key professional fields—not because it’s ready, but because we’re not prepared to stop it.

Hey by the way this is part of a much longer series of AI pessimism at least eight years old.

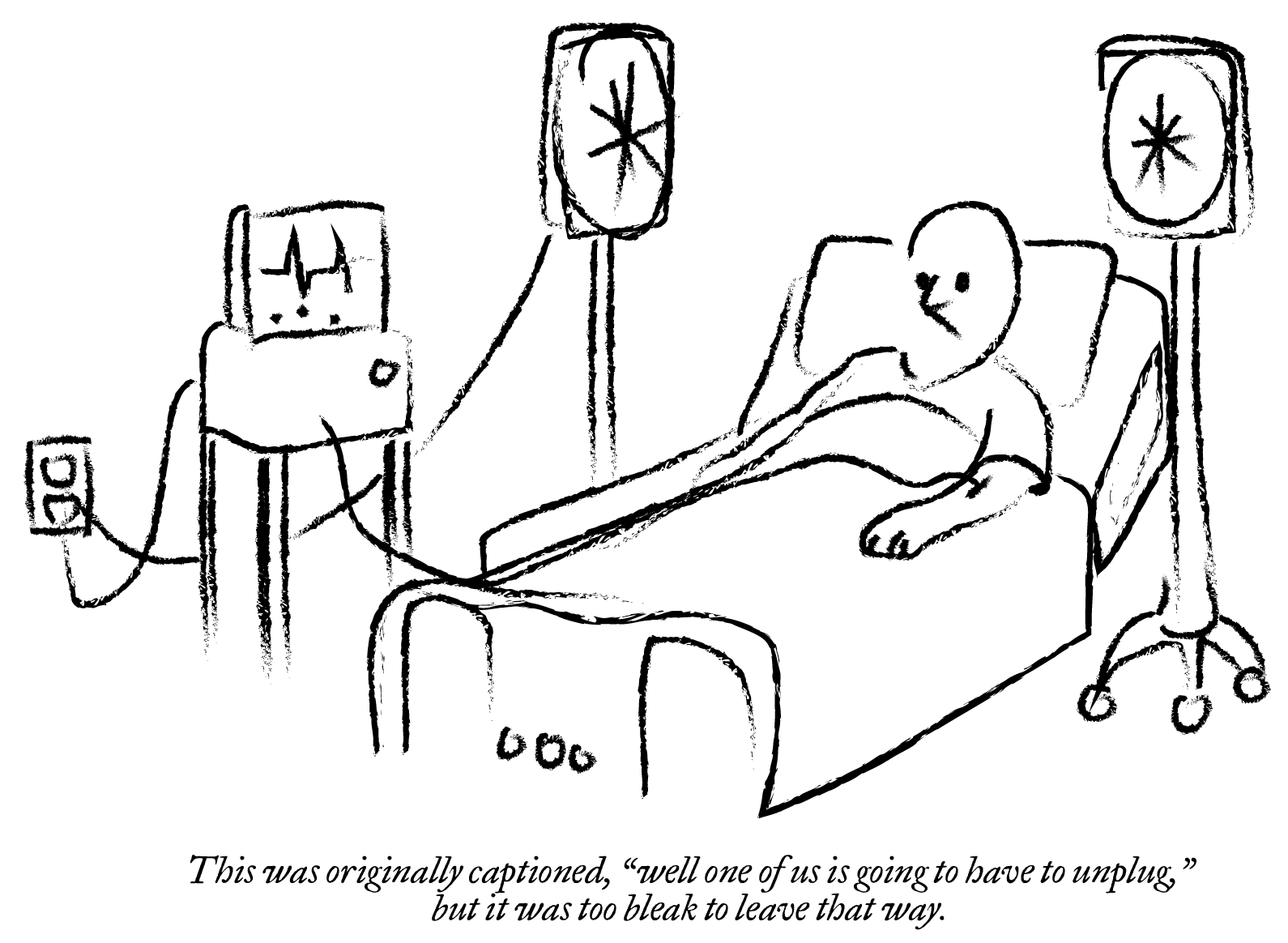

I’ve often suggested offhand that I expect AI doctors and lawyers to be common within five years. This prediction is based on the rapid growth of AI capabilities, especially in knowledge retrieval and chain-of-thought reasoning, but it is not an optimistic prediction. Instead, it reflects a failure of consumer protection and data privacy regulation.

I do not think many people will want an AI doctor in 2030. But I also do not think we will have a choice: This shift has already begun. Here’s how:

First, regardless of the proliferation of low-quality AI content on social media, deep learning models are actually extraordinarily good at certain types of tasks like diagnosis from radiology and indexing and accessing large amounts of text. For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that in five years, a multimodal foundation model could be a reasonable surrogate for at least a “first-pass” triage of a medical case or legal question. (There are a lot of reasons to imagine this inflection point is already well in the past.)

The real problem is that there are catastrophically misaligned incentives between the patient and the hospital administrator. The American hospital administrator thinks first about revenue, which takes the form of insurance payments and government reimbursements.

There are laws governing the use of algorithms in place of healthcare practitioners. For example, some regulations prohibit treatment without a human confirming the plan. But there are currently no such laws governing the use of algorithms to approve or reject treatment plans at insurance companies (and it is of course already happening). Thus, an insurance company today could use ChatGPT to determine which treatments to reject. From there, it is a short step to the insurance company offering an API—at a cost, of course—so that the hospital can submit a treatment plan before treating the patient and see if the insurance company will cover it. This situation now describes an AI chatbot—not even one under the purview of the hospital — making determinations about the course of patient care. This is legal today, and insurance companies already certainly are using chat models to retroactively explain decisions, if not make them outright.

In the legal system, the economic gears are turned not by insurance company payments, but by apprentices who operate a large volume of the legal and administrative apparatus. The ecosystem involves paralegals apprenticing at law firms before or during law school, gaining years of experience that make them valuable to a law firm even before they step foot in a law school classroom.

It is likely that this type of research and administrative role will be complemented or replaced by large language models in the near future. Scheduling emails, searching for relevant documents—these are tasks that chatbots can already perform effectively, despite some recent missteps.

This means there will be a significant reduction in the number of paralegal positions. Not everywhere, but many firms will compare the salary of a paralegal to the much lower price tag of a language model subscription, and determine that some parts of their workload could be outsourced to a chat bot. As a result, a generation of lawyers will graduate law school with, on average, less experience than previous generations.

Law firms looking to recruit new associates will then have to choose between hiring an “old guard” lawyer—expensive, and increasingly rare—or one of these newer graduates, who are less expensive but have much less experience. This “missing middle” problem will only intensify as AI models improve and the experience disparity between established incumbents and novices increases.

The implications for both professions — and beyond — are serious. The same “missing middle” applies to software developers, academics, and business executives. As AI systems become more capable and entrenched in decision-making processes, the traditional pathways for gaining expertise and experience will erode. Without careful oversight and adaptation, we risk creating a future where critical decisions are made by algorithms with little human context, and where the next generation of professionals lacks the depth of experience that has long defined these fields.

Anyway that’s how I’m feeling these days.

From my post nearly eight years old at the time of publishing this article:

We, as the inhabitants of the 21st century, have an immense responsibility to our posterity to point our technological weapons at disease; at hunger; at conflict. But for fuck’s sake, please do not point technological weapons directly at your eyes or ears. And absolutely do not point them at mine.