Kepler kind of beat Newton to gravity I think?

I mean… kind of? Not totally? But it definitely seems to me like Kepler figured out some pretty fundamental attributes of gravity that we usually attribute to Newton, and they wound up in the footnotes of a not very popular book, and so now nobody talks about it at all.

I don’t remember how it arrived on my To-Read radar but I got my hands on a copy of Kepler’s Somnium (latin for The Dream).1

Cover page of the 1634 edition of the Somnium. The distortion is because I took a scan of the 1967 edition of Edward Rosen’s translation. If you use this image, please make sure to take a low-quality screenshot and include some distortion of your own. This is called science.

People call Somnium the first work of science fiction, since it’s about the daemons who live on the moon, but it’s practically an educational text complete with 223 footnotes (which far outspan the actual text), explaining his science, writing, and rationale.2 Kepler wrote it during his dissertation at Tübingen in the 1590s as a way of trying to convince his professor of his theories on the motion of the planets, but his professor refused to hear it. So Kepler saved it for later, and published it with some zesty jabs at his professor’s dogmatic orthodoxy.

I mean, just. This book is delicious like that.3 To wit, there’s also a great deal of glowing admiration for Tycho Brahe in the text;4 it just goes to show how influential a good teacher can be.

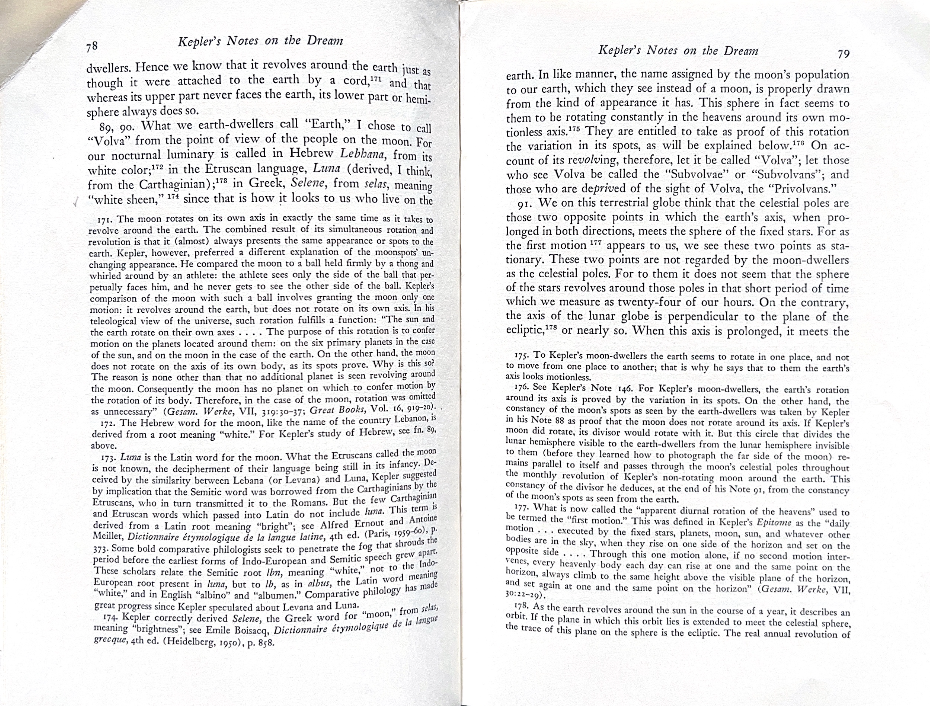

Reading the Rosen edition, with its footnotes-upon-footnotes, feels like trying to move through Danielewski’s House of Leaves, except it’s unintentional and all the footnotes are true and nearly half a millenium older. Check this out:

Footnotes upon footnotes. Pictured here is the “notes” section of the book, which is several times longer than the actual text. And beneath Kepler’s footnotes (e.g., 89, 90 describing the unfortunately-named “Volva” alias for the Earth) are Rosen’s footnotes (e.g., 171, 172…) which themselves are several times longer again than even the first set of footnotes. Don’t even get me started on the Appendix, which has its own Appendix.

Wait sorry, I’m losing the thread here.

In general, people credit Newton not with the “discovery” of gravity5 but with the mathematical explanation of gravity. In the 1687 Principia Mathematica, he describes the law of universal gravitation with three key characteristics:

- …as a force, which is to say, an invisible action induced by a mass at a distance

- …unified across scales, that it applies to both celestial (moon) and terrestrial (apple) bodies, regardless of their size or makeup

- …as an inverse-square law, that gets weaker predictably with distance

But as you move through Somnium, it becomes increasingly clear that Kepler likely already had a private mental model of these principles (in the 1610s; long before Newton’s Principia, first published in 1687).

1. As a force

“I define “gravity” as a force of mutual attraction, similar to magnetic attraction. But the power of this attraction in bodies near to each other is greater than it is in bodies far away from each other. Hence they offer stronger resistance to being separated from each other when they are still close together.”

Note 66 (p. 71, Rosen)

Kepler states in his New Astronomy that gravity could be described as “a mutual corporeal tendency of kindred bodies to unite or join together.” This was already somewhat a revolution upon a revolution; Copernicus had already proposed that the Earth was not the center of the universe, but still seemed to maintain that the Earth had a “certain natural striving” to be spherical, having nothing to do with gravity, but just because spheres are cool. (Copernicus, already a revolutionary foil to Aristotlean geocentrism, even considered that the Moon and Sun were spherical for the same reason.) As far as I can tell, Kepler is the first to suggest the force-based formalism here.

2. Unified across scales

In Note 66 of Somnium Kepler describes gravity as a force of mutual attraction, but now finally without the restriction of “kindred” bodies. Did he just leave it out of the notes, or did he truly appreciate the universality of gravity across all matter?

Here’s why I think he was already onto universal gravitation a la Newton:

“[The human travelers] roll themselves up into balls … which we [daemons] carry along … so that finally the bodily mass proceeds toward its destination of its own accord [‘sponte sua’].”

(p. 16, Rosen)

This is a pretty clear indication that the travelers — human sized, after all — are affected by the recipient lunar gravity. And if this effect was indeed a “mutual tendency” like Kepler describes, then the moon’s gravity would be pulling on the travelers as well as the travelers pulling on the moon.

Later in the Somnium,

“the causes of the ocean tides seem to be the bodies of the sun and moon attracting the ocean waters by a certain force similar to magnetism.”

Note 202 (p. 219, Rosen)

Most certainly the ocean is not the same thing as a planet, as far as Kepler was concerned. Kindred? It seems unlikely Kepler would have felt so.

1. Inverse-square law

From New Astronomy:

“Suppose that somewhere in the universe two stones were put near each other, yet outside the sphere of the force exerted by any third kindred body. … Those stones would come together at an intermediate place. As each one approached the other, the distance traversed would be in proportion to the other’s size.”

(p. 220, Rosen)

On the Earth and Moon (also from N.A.), were it not for their orbits:

“the earth would rise toward the moon one of the fifty-four parts of the interval between them, and the moon would drop toward the earth about fifty-three parts of the interval.”

(p. 220, Rosen)

Kepler even specified the dynamics of that system to a friend upon the publication of N.A. in quite clear terms:

“They will divide the intervening space in the inverse ratio of their weights.”

(p. 221, Rosen)

It is most definitely true that Kepler did not arrive at the same mathematical rigor or formality that was later achieved by Newton. But these properties — the force of gravity, the universality of gravity, and the falloff with distance — are all present in Kepler’s work (1630, at the absolute latest) many years before Newton was even born (1642).

But they’re present in a little book in an even littler footnote, and that’s not very much mass at all, and so it doesn’t attract very much attention from kindred bodies.

-

It almost certainly came from a recent watch-through of Terence Tao’s video with Grant Sanderson on the Cosmic Distance Ladder, which you should watch if you haven’t already. ↩

-

Kepler explains in his Note (#51) that the modern word “daemon” derives from the Greek “daiein”, “to know.” Rosen explains in his own footnote (#121) to the reader that, no, it definitely does not. And now you’re reading my footnote about Rosen’s footnote about Kepler’s footnote and now we’re all daiein of laughter. ↩

-

From Note 9: “In like manner most people expiate their love of science by being poor and incurring the hatred of the ignorant rich.” (p. 43, Rosen.) Come on, you could really get a beer with this guy. ↩

-

Kepler would eventually be Brahe’s apprentice and inheritor of the title of Imperial Astronomer. But in the meantime, a lot of Kepler’s early letterwriting to his contemporaries mostly amounts to, ‘cool, glad you’re doing great, hey anyway have you heard anything new from Tycho recently, do you know if he asked anything about me’, etc. ↩

-

Like. I hate to do this, but this is a real “hi hungry I’m dad;” obviously people knew about gravity before Newton. ↩